Motivation to Die For: James Clear, Ryan Holiday, Bronnie Ware, and Oliver Burkeman Walk Into A Bar

Guru stacking for a lifetime of motivation

At some point in your life you have likely pondered how you might become more motivated. We’ve all had our moments of uninspired living, listlessness, boredom, wasting time scrolling on social media, and avoiding even the things we’d enjoy doing or would like to accomplish. Why is that?

Some people say trying to find motivation is the wrong approach, because motivation is just a feeling that comes and goes, or it only shows up after you start something, not before, thus is not a reliable driver of forward progress. Fair enough, but what then propels life if we have no underlying motivation? Why do anything at all?

I once heard a motivational speaker tell the story of being in a near-death car accident. That incident set him on a course to do something worthwhile with his life, leading to the work he does today. While I found the story profoundly moving, I was at a loss as to how I might apply this in my own life. I had no “inciting incident” to propel me to a life of fulfillment. Should I try to get into a car accident too?

A few years ago I stayed in an AirBnB in a city where a Tony Robbins event was happening. A young lady at the same AirBnB had flown in to attend the event. I ran into her afterwards, and asked how it was. She said she had been to many Tony Robbins rallies, because they are extremely motivating, and goes to see Tony whenever she can. She was jumping from one “You can do it!’ session to the next, to keep “refilling” her motivational tank. I wondered how many events one must attend for the motivation to stick in such a way that you no longer need the refills? Following Tony around the country does not strike me as a good plan. What will you do when he retires? I want something more durable, that does not decay over time, and is not reliant on someone giving me an inspiring speech every week.

I grew up in Chicago during the Michael Jordan era. He was the king of the city for many years. He was intensely competitive, driving him to become one of the best basketball players of all time. He had what I call “competitive revenge” motivation, where he looked for any slight, any taunt, any trash talk from opponents as a reason to turn them into enemies deserving of a beating on the court. This type of motivation produced extraordinary results, but with one devastating downside: everyone hates you, even your own team mates. I would love to be the GOAT (greatest of all time) at something, but not if it means I have no more friends and a ruined reputation. Sorry not for me.

Have you heard of Jonny Kim? He went to Harvard and became a surgeon, Navy Seal, pilot, and NASA astronaut, all before age 40. He grew up with a violent, abusive father. Part of his intense drivenness to excel comes from growing up in an environment where any wrong move was punished, wanting to prove that he’s not worthless, and somehow earn his now deceased father’s approval and love. It unfortunately gets glossed over in the easy-listening podcast interviews, but many famous extreme high performers are driven not necessarily from a healthy place, but one of desperation to reverse the esteem-crushing effects of being abused. But instead of understanding the deep implications of this, we want to know their morning routine.

I could go on with other motivational sources, but you get the point. Most of the motivational content in the world today is unique to the individual, non-reproducible, inapplicable, superficial, temporary, or not at a depth level that creates real change in everyday people.

The reason the “self-help” motivation industry is worth billions of dollars, with no end in sight, is because most of the advice out there simply isn’t working, but people desperately want to find something that does work. So they try this guru and fail, then the next guru and fail. And the high failure rate is usually because the person giving the motivational advice has a unique life that created their source of motivation, which is simply not reproducible in anyone who has not lived the same life. Yet the speaker believes it can be. It worked for me so it can work for you too! You just have to be willing to put in the work! You just have to hustle! If I can do it, anyone can! Eager listeners try and fail to produce the same world class results as their favorite pro athlete or entrepreneur, but it never works, otherwise we’d all be world class performers. What worked for one highly successful person probably won’t work for you.

I like a rousing speech as much as the next person, but deep down inside I know that whatever is being advised won’t work for me. So what to do? How can regular everyday people find motivation?

After many years of trying and searching, I’ve assembled something for myself that is challenging me in a tangible, durable, and lasting way. If you’re someone who also finds all the simplistic cheerleading advice on Youtube to just “start by setting a goal” useless, maybe it will help you too, because I am not a naturally intrinsically motivated person. I am not a world-class performer at anything. I am a chill, laid back person. But I still want to accomplish some things in life, and often struggle to do so.

The paradigm I’m about to share is meaningful, purpose-aligned motivation to last a lifetime, not just a weekend. And I think it is more universally applicable than nearly all the motivational techniques I’ve seen, as the components within it are true for everyone.

In classic Octopus generalist fashion, it is not found in any one guru’s theory, but rather a combination of ideas, that when put together, are more potent than the parts.

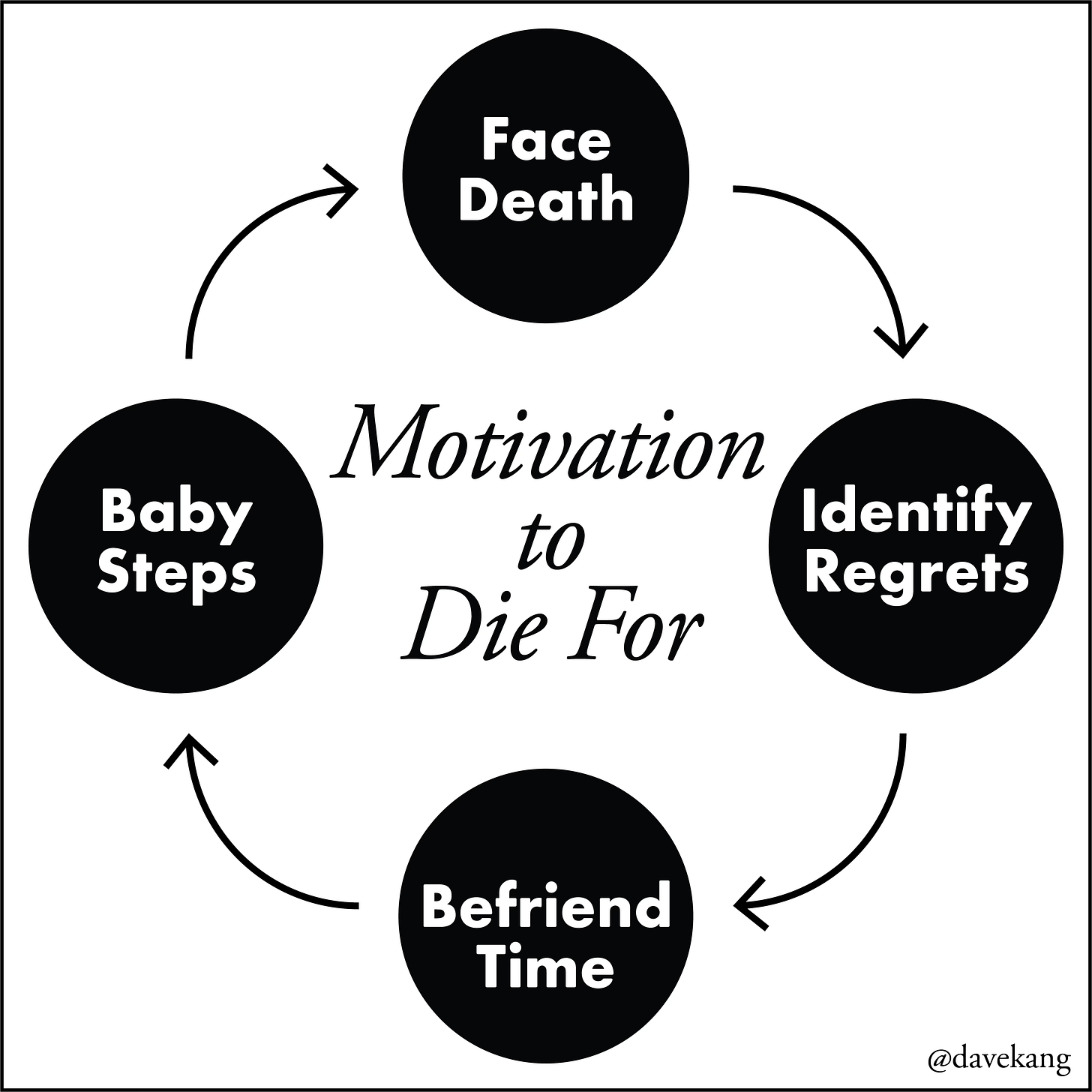

I call it “Motivation to Die For”. I built the theory upon the work of four amazing authors: Ryan Holiday, Bronnie Ware, Oliver Burkeman, and James Clear.

Let’s walk through these one at a time:

Ryan Holiday is the author of books on stoicism such as Ego is the Enemy. From him I learned about Memento Mori, a Latin phrase that translates into “remember you will die”. A bit morbid, isn’t it? Fans of Stoicism use this to ponder their mortality, and make strategic choices about what to do with their lives.

Bronnie Ware is the author of The Top 5 Regrets of the Dying. As a palliative carer working with dying people, she captured the most common final regrets of people on their deathbed, which are:

1. I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.

2. I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.

3. I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings.

4. I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends.

5. I wish I had let myself be happier.Oliver Burkeman is the author of Four Thousand Weeks, which refers roughly to the number of weeks in a typical lifespan. He writes about taking a long term view and reframing how we look at time, so that we might use it wisely and intentionally, rather than letting it fritter away.

James Clear is the author of Atomic Habits, a book about habit formation, with advice on devising systems and techniques to execute the small habits that lead to life change.

I don’t remember everything written by these authors, but have you heard the phrase, “People won’t remember what you said, but they’ll remember how you made them feel.”? Well the following theory is based on how these people made me feel.

I’m sure if I sat down with these authors they would have much more to say than the buckets I’m about to put them into, but here’s my simple “Motivation to Die For” theory:

We don’t want to face our own mortality so we do all kinds of things to distract ourselves and avoid thinking about death, much to our detriment, because doing so often leads too…

Weeping and gnashing of teeth on our death beds, regretting all the things we never did. To avoid this, we should…

Change our relationship with time, befriending it and owning it, rather than letting it get away from us, and use it wisely to…

Execute repeatedly on little things that specifically target our regrets, so that over time those regrets evaporate, and turn into accomplishments.

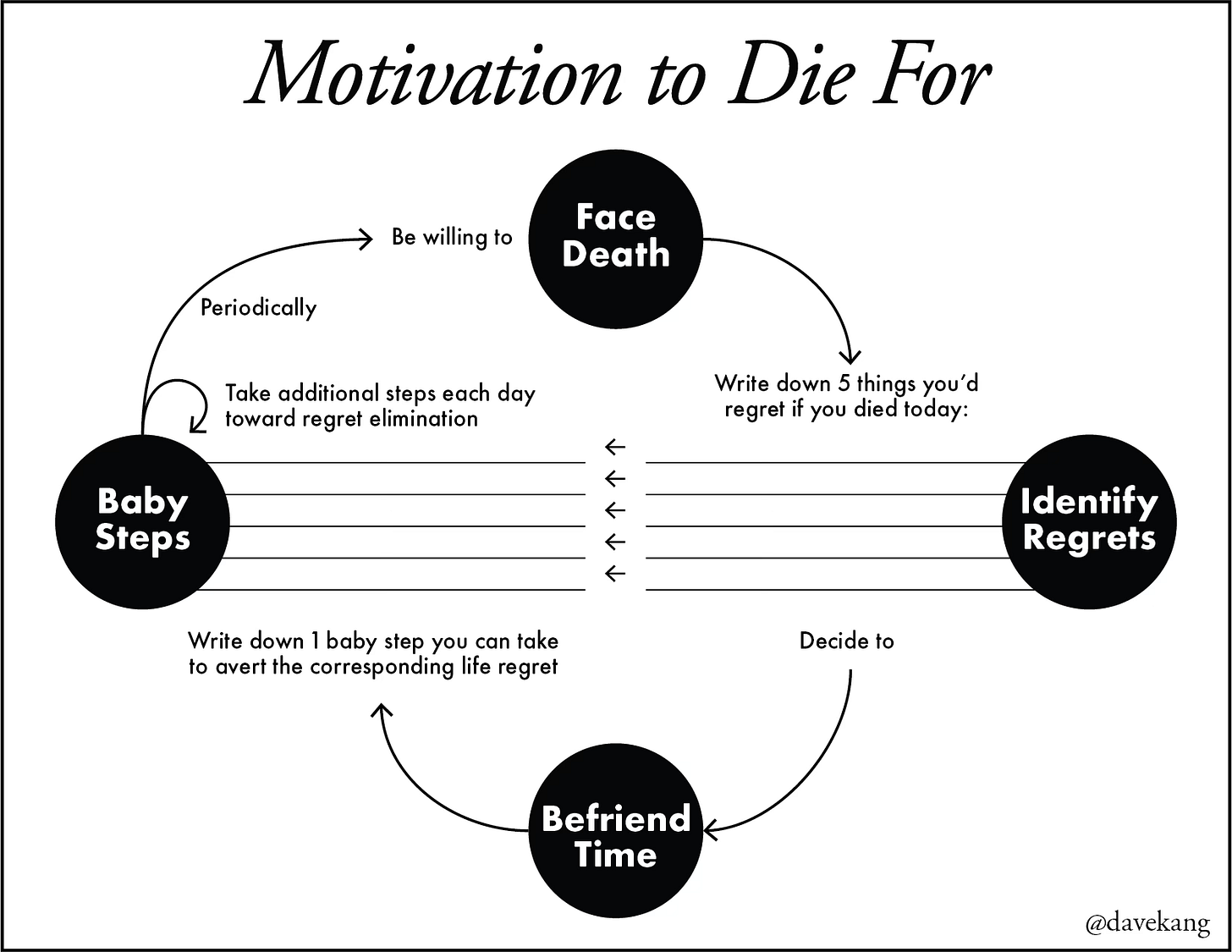

Here’s a visual:

Do I really have to think about death?

When I first heard about Memento Mori, I didn’t like it. Who wants to think about death? How depressing and anxiety producing! Do we really need it to motivate ourselves? But the more I thought about it, the more I liked it, for one primary reason: it is the “end game” event of our lives. The final boss. Unlike a car accident, “ra-ra” motivational rallies, or a trash talking opponent that pump you up temporarily, death as a motivator will last a lifetime.

Why is it important to think about deathbed regrets?

Another depressing topic! No one wants regret in their life. I’m not even on my deathbed and I already have life regrets! But the power of deathbed regrets is incredible. Unlike trying to come up with happier positive aspirations and goals, which can be any number of mis-aligned things clouded by delusions of wealth and grandeur, deathbed regrets are the ultimate forcing function, distilling in reverse what you really want out of life. They help get to the bottom of what you really should be doing, instead of those fleeting desires and new year’s resolutions inspired by something you saw on Instagram.

Why do we need to befriend time?

As long as we think of time as the enemy, we will always be fighting against it, wishing for more of it, and stressing out about not having enough of it. Time is what it is. You can’t buy more of it, slow it down, or speed it up. So why not make friends with it? Accept it for what it is. I like the idea of “befriending” better than phrases like “managing” or “controlling” or “being more efficient” with time, because all those approaches have tyrannical connotations, where you’re trying to grab the time bull by the horns and squeeze the life out of it. Befriending implies a symbiotic relationship, where you work with time, letting your life flow with it like a raft down a river instead of fighting it.

Why do we need Baby Steps?

The journey of 1000 miles begins with one step. Popular books like Atomic Habits and Tiny Habits have shown that small repeated actions can be effective at creating incremental life change. You have to start somewhere, and if you start too big, you will likely fail. Starting small gives you a sense of accomplishment, something to celebrate each day, and compounded over time, can change your life, one baby step at a time.

How can I use this theory in my life?

I’ve made 2 tools to help materialize the theory. The first is a worksheet that you can download here. It’s a simple exercise to work through the model, and figure out what you should be doing with your life at the highest strategic level, and what you should be doing with your time at the lowest atomic level:

We begin at the top of the diagram, and make a willful choice to face death, acknowledge that it will come to us all someday, until we no longer fear it.

Without this acknowledgment, it is hard to proceed to the next step, which is to imagine yourself on your deathbed, and identify what your top 5 particular life regrets might be.

Once you have those in hand, the next step is to befriend time. Accept that you have a limited amount of it, decide to work with it towards addressing your 5 regrets, and choose to flow with it rather than fight it.

Next you will take your 5 regrets, and come up with corresponding baby steps that specifically begin to address and chip away at your regrets. You will keep taking new baby steps until you have essentially reversed those regrets into achievements. At the end of your life you will no longer have regrets, because you addressed them while you still had the chance.

Sometimes people don’t know what they should be focusing on in life. By identifying your five end of life regrets, you will know the most important things that matter to you. By identifying five matching baby steps, you will know that you are working on the most important things that you could be doing today.

As an example, here are my 5 Regrets:

I wish I had let myself be more creative.

I wish I had become a successful entrepreneur.

I wish I had better relationships with family and friends.

I wish I had helped more people along the way.

I wish I lived more courageously.

And the corresponding Baby Steps for this week:

I will post my calendar project on Pinterest.

I will work this week to make my consulting client’s campaign amazing.

I will call one of my friends this weekend.

I will answer every comment on Substack with kindness and try to be helpful.

I will stop looking for a full time job and embrace the entrepreneurial unknown.

After you do a baby step, repeat with a new baby step. Keep executing baby steps that reverse engineer your regret. Over time you will make tangible progress towards eliminating your regrets completely.

Over time, as you get older, your life regrets will likely change. The things you regret when you’re 25 will likely be different than at 50. So periodically you will revisit this entire cycle to make sure you are still aligned. No matter what age you are today, you will know you are working on the things that matter the most right now.

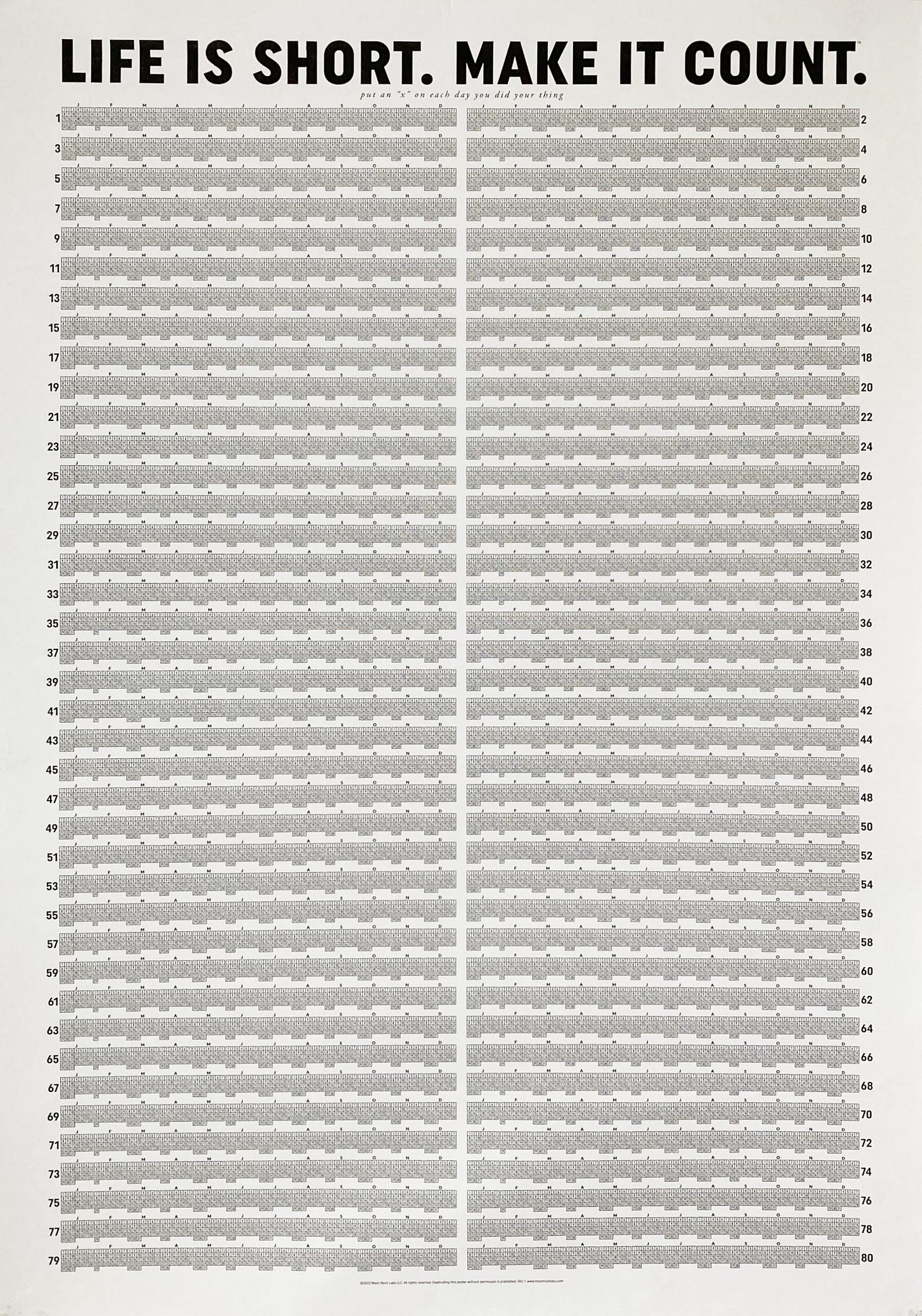

The second tool I created is a “Life at a Glance” calendar, that shows you every day of your life in one view, for 80 years:

This calendar encourages you to face death, befriend time, and track your baby step progress, so you can ultimately eliminate your life regrets. Put it on your wall for a daily reminder to stay focused on your chosen steps, and to consider the regret-filled consequences of failing to make progress at the end of your life.

Some people have told me this calendar creates anxiety, as it’s overwhelming and also scary to see life laid out in such stark, finite terms. I understand that, but which anxiety would you rather deal with: the anxiety of acknowledging your eventual death now, that can inform changes while you still have the chance, or the anxiety of reaching your deathbed having failed to do the most important things you wanted to do in life? I would argue the deathbed anxiety from a life of regrets is worse.

If you want a calendar, it’s available now on Kickstarter until Jan 5.

I hope you find this motivational model thought provoking, it certainly made me uncomfortable at first, but as I faced it, embraced it, and pondered it, the model evolved from anxiety to empowerment. It has helped me rethink a lot about how I spend my time. When I’m doom scrolling social media, I look at my calendar and ask myself if this is really how I want to spend today, a day I’ll never get to live again? When I work on my business or call a friend, I know I am taking small, real steps each day that I know will help me avoid deathbed regrets.

To summarize:

There is no motivation source more durable than pondering death.

There is no focusing function greater than identifying deathbed regrets.

There is no better way to alleviate time tyranny than befriending it.

And there is no life progress without a series of small action steps.

Let me know what you think in the comments, will this motivational framework work for you?

Dave

When the student is ready, the teacher appears. And man, did you time this right. Your article really hit home for me. Something I'd like to add, when truly facing your regrets, it also creates an opportunity for gratitude, for the things you did right, for the choices you made that were the right ones. I'm going to pledge to your kickstarter, and look forward to getting my calendar in the mail. (speaking of which, there's a postal strike up here in Canada, just fyi). I only need the last chunk of it (!) but that just makes it all the more urgent. thanks for this, Dave. it's just what I needed.

"Regrets are insights come too late" -- Joseph Campbell

Good stuff as always Dave. 👏 Check out Ernest Becker's "The denial of death" for more about how we distract ourselves from our own mortality.

Rather than thinking about death, using something like your BIG calendar to drive home the finiteness of our life time is a better approach. Dividing life up into four 20 year chapters provides interesting focus and motivation.

Your crisp visuals are very useful to people. Keep goin'!